Spherical Harmonics and surfaces, an attempt

Martino Trapanotto / April 2024 (2925 Words, 17 Minutes)

Instead of starting to work on my master thesis, I decided to read a bit about Gaussian Splatting, a new technique to create high quality 3D scenes from just a few shots, with real time rendering. As I read some code and papers, I kept noticing references to Spherical Harmonics, which I hadn’t heard about before.

So as an aside to the aside, I tried reading the Wikipedia page, understanding very little. So I delved a bit deeper

Spherical Harmonics: An intro

After some false starts at the hands of formal definitions and abstract mathematical descriptors, I managed to find something to ease me into the ideas1, developing a decent intuitive understanding of the key concepts2, and managing to actually read some of the aforementioned math3. Not too in depth, we’re cool here, we make colored shapes and play with 500€ toys. For more math see 4 5 6.

In pretty broad terms, Spherical Harmonics translate the ideas of decomposing a function through Fourier Transform from 1D functions into 3D sphere surfaces.

So if in 1D functions we can split any function into infinite combinations of sines (or cosines or a lot more), we can do the same here for any function that works on the surface of the sphere.

An example of this kind of function might be how an antenna emits radio waves in various directions, or the brightness of a spherical image, or the shape of a convex surface. We’re associating a value (height, power, light) to a direction in spherical coordinates.

More mathematically, Fourier transforms allow us to move from an function space into another space defined by the orthonormal bases we use, traditionally that is the one constructed by function. But you could use any basis, such as square waves or wavelets, they only need to follow some specific properties.

Spherical Harmonics move this topic form onto , which descrives the surfaces of n-dimentional spheres. I think the main difference is in how the edge of these surfaces differes from the inifnity of , and this leads to a different orthonormal basis. $

Here are some formulas, for producing the coefficients:

and for reconstruction:

You might not encounter them often, but they’re very useful in some physics, especially quantum, as they are useful to solve a bunch of equations I do not understand, Geodesics, to describe the gravity of the earth at each position, as it’s not actually uniform and is very important in stuff like space applications, and in graphics to store a bunch of effects and lightmaps and more efficiently. Similarly, the original usage of Fourier transforms was to solve the equations of how heat propagates into materials, and in general differential equations, not for signal processing.

So we can decompose this surface into combinations of the Spherical harmonics, much like sine waves. Harmonics don’t have the same nice interpretation of sines for sound, but the idea is the same, and it can be used for many similar usages: compressing a surface into a limited number of points, removing some types of noise or defects, or solving differential equations.

In my original question, I think that harmonics are used to store more complex effect like reflections and other surface properties in a more efficient way, as they can be quickly computed based on angles and a few parameters, which can in urn be learned by gradient descent on known views of the environment, compared to using materials or other methods to differentiate optical properties.

But at that point I wanted to do more than just reading, I wanted to build:

Displaying Harmonics

Spherical Harmonics have two parameters, usually and to identify their order, and then they are functions of the two spherical angles, and . There are analytical formulas to describe them for an arbitrary order, but they’re a bit outside the scope of this quest for now, so I just took the formulas of the real versions from Wikipedia’s table and coded them in Lua.

Then I used lovr-procmesh to load a sphere model and mapped each vertex to draw the basic harmonics.

harmonics[l][m] = normalize_surface(sphere_model:map(

function(x, y, z)

local r = math.sqrt(math.pow(x, 2) + math.pow(y, 2) + math.pow(z, 2))

local theta = safe_theta(z, r)

local phi = math.atan2(y, x)

r = return_SH(l, m, theta, phi)

x = r * math.sin(theta) * math.cos(phi)

y = r * math.sin(theta) * math.sin(phi)

z = r * math.cos(theta)

return x, y, z

end

))

Here return_SH returns the real valued components of the corresponding harmonics, I just copied the formulas from Wikipedia’s page

I only wrote the first three orders, which is barely enough to draw non-trivial surfaces.

Decomposition and reconstruction

But my big idea was decomposing and reconstructing a surface using this limited set of harmonics, to see how the lower resolution would impact it.

So, we need to compute the coefficients for each harmonic, and then recombine them to reconstruct the surface.

Easy, right?

In code we make

The complex conjugation is irrelevant in the real component, so no problem.

But the needs some attention.

It’s the solid angle of the integration, and in the code I am copying taking inspiration from3, it’s calculated as a variable coefficient of .

The article does not really explain this, referencing only a projection model it takes for granted, so I had to solve this for my models.

Sampling and models

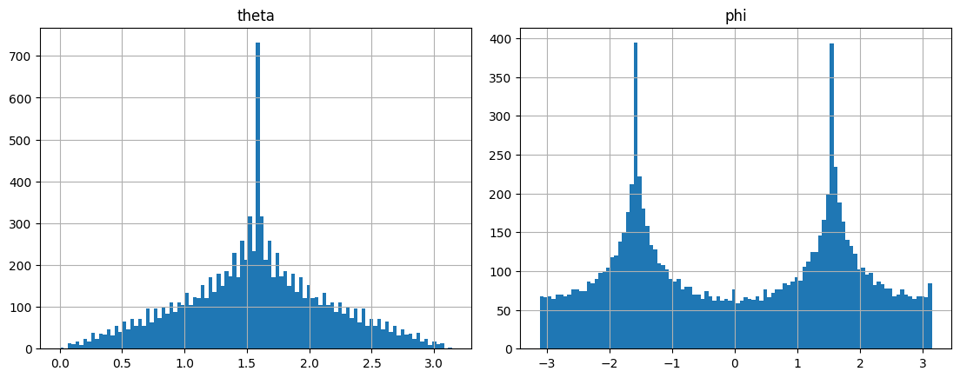

To cut it short, the model I’ve been using at the beginning has an odd distribution of vertices on the two angles. This non-uniform distribution surely influences the integration step, creating these weird results.

Instead of correcting for this and, lovr-procmesh has another method to generate sphere meshes. These are actually uniform, so we can simply use .

The code to decompose into parameters is

n_vertices = #surface.vlist

print("N Vertices on surface: ", n_vertices)

solid_angle = 4 * math.pi / (n_vertices)

maxl = 2

parameters={}

for l = 0, maxl do

parameters[l] = {}

for m = -l, l do

parameters[l][m] = 0

end

end

for index, vertex in ipairs(surface.vlist) do

local x, y, z = vertex[1], vertex[2], vertex[3]

local r = math.sqrt(math.pow(x, 2) + math.pow(y, 2) + math.pow(z, 2))

local theta = safe_theta(z, r)

local phi = math.atan2(y, x)

for l = 0, maxl do

for m = -l, l do

parameters[l][m] = parameters[l][m] +

(r * return_SH(l, m, theta, -phi) * solid_angle)

end

end

end

And to reconstruct

reconstructed_surface = sphere_model:map(

function(x, y, z)

local r = math.sqrt(math.pow(x, 2) + math.pow(y, 2) + math.pow(z, 2))

local theta = safe_theta(z, r)

local phi = math.atan2(y, x)

r = 0

for l = 0, maxl do

for m = -l, l do

r = r + (parameters[l][m] * return_SH(l, m, theta, phi))

end

end

x = r * math.sin(theta) * math.cos(phi)

y = r * math.sin(theta) * math.sin(phi)

z = r * math.cos(theta)

return x, y, z

end

)

So the result is…

Yay! We can decompose arbitrary surfaces now and reconstruct them somewhat

The ones on the left are composed only based on the available harmonics, so they are supposed to be fully reconstructed, apart from negative valued surfaces. The right ones are instead randomized based on a website I found. They can’t be reconstructed accurately, but they do look kinda similar…

You can find the rest of the code on GitHub

-

https://irhum.github.io/blog/spherical-harmonics/index.html ↩

-

https://justinwillmert.com/articles/2020/notes-on-calculating-the-spherical-harmonics/ ↩ ↩2

-

https://lmb.informatik.uni-freiburg.de/papers/download/wa_report01_08.pdf ↩

-

https://blog.42yeah.is/light/rendering/featured/2023/01/07/spherical-harmonics.html ↩

-

http://scipp.ucsc.edu/~haber/ph116C/SphericalHarmonics_12.pdf ↩